The European Framework for Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence (LifeComp) and what it could mean for adult education and learning.

This article was first published on EPALE: https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/blog/lifecomp-competences-life-and-learning-times-transition

We live in a time of transition, which makes demands on us both as individuals and communities. Changes to society caused by migration, the rapid transformation of the world of work due to digitalisation, and the transition to climate-neutral economies are just a few examples. We need more than just new skills and knowledge in certain areas if we are to master and help shape the ensuing challenges. We need wide-ranging competences that equip us to deal with the most diverse circumstances.

Aims of the LifeComp framework

The LifeComp framework wants to do justice to these various challenges. It describes nine key competences, some of which focus more on inner preparedness, while others are more action-oriented. Together, they present a holistic picture of transversal competences for continuing personal and social development. LifeComp is a conceptional framework; it is neither normative nor a qualifications framework. It aims to create a shared language and structure for implementation in various contexts, regardless of age or stage of life. In this way it can provide a foundation for preparing teaching plans and learning activities and be introduced in formal, non-formal, and informal education settings.

LifeComp structure

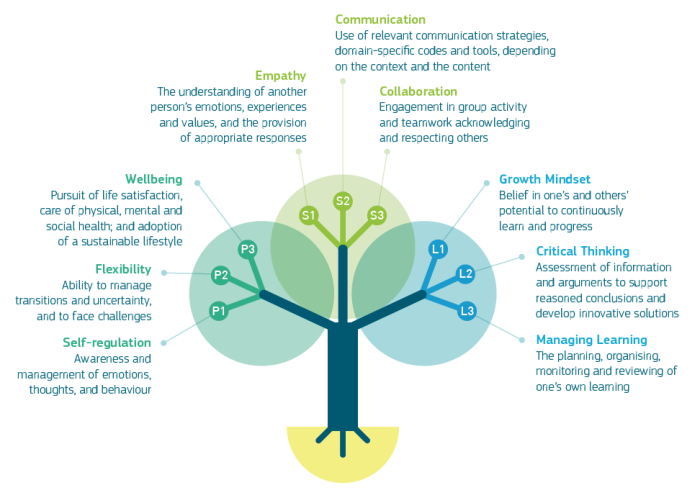

The framework is divided into three areas: personal, social, and learning to learn. Three competences are attributed to each area. Here is a brief overview:

Structure and definition of the competences

Personal area

- Self-regulation: awareness and management of emotions, thoughts, and behaviour

- Flexibility: ability to manage transitions and uncertainty, and to face challenges

- Wellbeing: pursuit of life satisfaction, care of physical, mental and social health, and adoption of a sustainable lifestyle

Social area

- Empathy: the understanding of another person’s emotions, experiences and values, and the provision of appropriate responses

- Communication: use of relevant communication strategies, domain-specific codes and tools, depending on the context and the content

- Collaboration: engagement in group activity and teamwork acknowledging and respecting others

Learning to learn area

- Growth mindset: belief in one’s and others’ potential to continuously learn and progress

- Critical thinking: assessment of information and arguments to support reasoned conclusions and develop innovative solutions

- Managing learning: The planning, organising, monitoring and reviewing of one’s own learning

Transversal and growth-oriented competences

The areas and their respective competences are presented in a nuanced way and their importance as key competences is explained. Connections to other competences and frameworks are often mentioned. Concerning “Flexibility”, for example, reference is made to EntreComp (European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework), which describes this competence in more detail. With respect to “Communication” – which considers both digital, asynchronous communication and face-to-face communication – reference is made to the DigComp Framework.

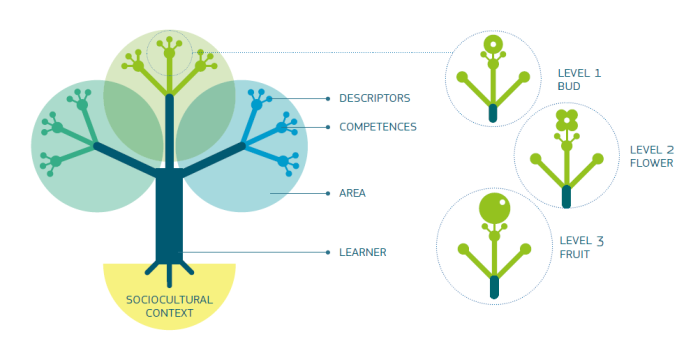

The tree metaphor is intended to illustrate both how key competences are geared towards personal growth as well as the competences’ interdependence. The earth and LifeComp tree’s roots indicate the socio-cultural context in which personal development takes place. The way in which competences are acquired is, of course, influenced by how supportive or obstructive this context is.

Competence model: Awareness, understanding, action

Each competence is explained in more detail using three descriptors that follow the model “awareness, understanding, and action”. To give an example, here are the three descriptors that accompany the competence “Wellbeing”:

- Awareness that individual behaviour, personal characteristics and social and environmental factors influence health and wellbeing

- Understanding potential risks for wellbeing, and using reliable information and services for health and social protection

- Action: adoption of a sustainable lifestyle that respects the environment, and the physical and mental wellbeing of self and others, while seeking and offering social support

The order of these descriptors is not intended to represent the sequence in which competences are acquired nor any kind of hierarchy. Rather, they are to be understood as competence dimensions in which competence development can take place. Unfortunately, this is contradicted by the visualisation of the descriptors using the tree, which clearly specifies specific levels, namely “bud, flower, fruit”.

This can easily create the impression that competences are acquired via a series of levels, analogous to language learning. However, an individual’s acquiring of competences, based on attitudes and personal experiences, does not fit easily into such a structure.

Competences as a key to life? A critical look at LifeComp

The LifeComp Framework is comprehensive; one is almost tempted to say: “written with great attention to detail.” The key competences are defined in a comprehensible and structured way. LifeComp was developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, JRC and received support in the form of advice from international academics and stakeholders, meaning the framework has a broad professional basis. However, in terms of overall assessment, some aspects are certainly open to criticism.

The individual as an infinitely adaptable and productive creature?

I think the definitions of the individual key competences make sense. However, taken as a whole, I get the impression that too much focus is placed on development for and adjustment to the labour market in the context of a smoothly functioning society. Employability, professional development, or making a contribution to the development of society as a whole are often stated as objectives; in other words, something that not only can but should be achieved when you acquire key competences. The description of competences is often followed by an “in order to”: You need key competences in order to act and teach well, solve problems, make satisfactory professional decisions, improve economic performance and social cohesion, create social or economic values, make effective progress, etc.

All of which is important and true. But in this way LifeComp abandons its descriptive, defining character and starts to resemble a catalogue of prescribed goals. If we managed to fulfil all goals, we would probably be able to seamlessly adapt to every professional and personal change and would also be active and respectable members of society. That may be desirable for some employers and the social status quo, as it would mean we were all independent, flexible, and permanently productive crisis managers. However, I fail to see how such results-focused competence acquisition is supposed to put people in a position to question or reject changes and develop and favour lifestyles and models that deviate from the norm.

Resilience: the new higher – further – faster?

LifeComp aims to strengthen resilience, which is the ability to cope positively and bounce back from adversity, uncertainty, and conflict. This is emphasised by references to the pandemic, such as: “In the current situation [July 2020], it is especially relevant that citizens be able to reflect on and develop their personal, social, and learning to learn competences in order to unleash their dynamic potential, self-regulate their emotions, thoughts, and behaviours, build a meaningful life …”1

Resilience is certainly a desirable quality in times of transition. However, I doubt whether acquiring competences and resilience in exceptional circumstances will mean that all individuals can meet new requirements in a very short time. To give an example: Europe experienced its first lockdowns in mid-February 2020, while the framework appeared in July 2020. Stressing the need to urgently acquire new competences after just four months assumes a tremendous rate of adaptation. Besides, it is possible to take a different view of the pandemic. Many people managed to cope with the new and difficult situation (even if they were not happy about it), new challenges were accepted, and a considerable amount of dynamic potential was unleashed – all without the LifeComp framework.

Without a doubt, we are seeing greater radicalisation in our society and, in general, a major lack of empathy and productive communication. If key competences are successfully embedded throughout the field of education, we can hope to at least temper these developments. It is also clear that many people struggled to cope. But a permanent focus on what individuals lack, such as sufficient resilience, does not strike me as the right approach to the situation. And do we really want a society in which personal growth and individual resilience are the key to solving all problems?

Single parents burdened by months of home schooling and working from home, people who are not allowed to be with dying family members, or those who lose all their possessions and loved ones in natural catastrophes, are allowed to struggle and must neither cope positively nor bounce back quickly from such experiences. In my view, a society should accept this and support those affected; its members should acquire competences which help them do so. Unfortunately, LifeComp does not go far enough in this direction. The way I read it, there is too much focus on individual crisis management. Those who do not succeed seem to be held responsible for their own “failure”.

LifeComp for adult learning?

Based on my points of criticism, questions arise as to the tasks and aims of adult education and learning. Of course we should equip people to deal with crises and changes in an appropriate manner and all LifeComp key competences can help with this. However, if we were to adopt what I see as an excessive focus on goals and optimisation, we would be reducing ourselves to a delivery service for the economy and a form of stress relief for all social and economic problems.

This does not correspond to my image of adult learning. Adult learning can and should promote the acquiring of competences which allow people to develop in their own way and learn for themselves. This involves more than just helping people to cope with change and remain functional in uncertain situations. Adult education can foster individual independence in both thought and action. And in this way we can increase the satisfaction people experience in personal development and participation in society. I am not saying that LifeComp does not envision all this. But the manner in which it is presented makes it hard for me to identify such an approach. Key life competences and their necessity can be described differently – namely, with a focus on people. An impressive example of this is the “Life Skills for Europe – LSE” project.

LifeComp for adult learning! What the framework could mean for adult education and learning

Notwithstanding my criticisms, I do believe that LifeComp is a major step in the right direction. For me, its main achievement is giving us a shared language. We in adult education can thus breathe new life into the discussion around competence orientation. Despite all efforts to put competences at the heart of our educational activities, we have not yet reached our goal. LifeComp offers a foundation. It is up to us whether we adopt its competences or, for example, add “creativity” (in the sense of the 4Cs: thinking outside the box). LifeComp also offers a basis for the discussion around how we can implement key competences in our education provision. After all, competence orientation requires more than just redesigning lesson formats.

It involves defining key competences as well as, for example, changing our approach to exams, with a shift away from true-or-false judgements of individual performance towards a more collaborative and creative approach. We can also think about new learning spaces and environments in order to promote the acquisition of competences, as the existing formats are often focused on the traditional teaching of knowledge and abilities. And as adult educators – regardless of whether we plan, advise, or teach – we should also take a look in the mirror: What is the situation regarding our own key competences? Are our organisations structured in such a way as to support competence acquisition?

I hope that LifeComp will be translated into many languages and thus lead to a lively discussion about key competences. Unfortunately, no one in Germany has so far taken on the task. That is a pity, as LifeComp gives us the chance to jointly shape a forward-looking approach to adult education and learning.

1. Sala, A., Punie, Y., Garkov, V. and Cabrera Giraldez, M., LifeComp: The European Framework for Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence, 2020. Page 8

The “LifeComp: Competences for life and learning in times of transition” article by Dörte Stahl is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. The linked works and the accompanying photos have their own licences. Please check before using.

Piture credits for the featured image: Stine86Engel, https://pixabay.com/de/photos/buch-leben-wissen-geheimnis-4302990/, pixabay.com